Love was the ultimate risk among slaves

Henry moved in closer to the window until he was standing only inches from her face. He couldn’t kiss Nancy, not with a cabin full of slaves just behind her out of sight. It wouldn’t seem proper…He was so close that he could feel Nancy’s breath on his lips. His heart was galloping, and his mouth was as dry as a desert. Their eyes locked, and Henry could see that she wanted him to do something, say something. Anything.

Before he even knew what he was doing, the words came tumbling out.

“Nancy. Would you be my wife?”Â

Nancy pulled back, stunned. Even Henry was shocked by the words that had just spilled out without warning. He couldn’t have been more surprised if a frog had hopped out of his mouth.

“You proposin’ marriage, Henry?”

* Â * Â *

Love is complicated enough without any of the constraints that slaves faced. And on this Valentine’s Day, it is only fitting to talk about the complications that made romantic love difficult for slaves like Henry Brown.

First off, Henry and Nancy had different masters, which was a formidable obstacle. It was possible for a man and woman with different masters to marry, as long as they received permission. So Henry found himself in the unenviable position of having to make two proposals–the first to Nancy and the second one to Nancy’s master, Hancock Lee.

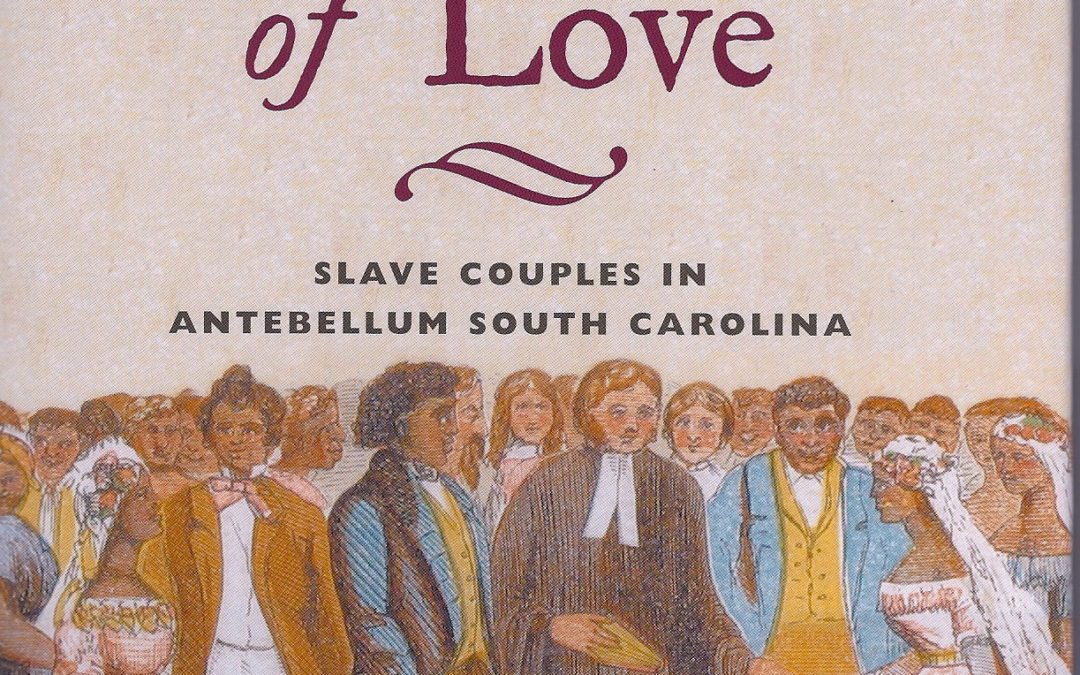

“Ultimately, owners possessed the authority to break up courting slaves as well as married couples, a power displayed most trenchantly through sales or separations,” writes Emily West in her book, Chains of Love–the primary resource on slave courting that I used for The Disappearing Man.

West tells the story of a slave named Mary-Ann, whose master forbid her from courting a certain slave–a “rascally fellow,” said the master, Mordecai Cohen. When Mary-Ann persisted in seeing the rascal, Cohen shipped her off to another plantation as punishment. He figured that grueling fieldwork would cure her.

Ironically, Cohen bemoaned the troubles that he had to endure because of this decision. According to West, “He emphasized the great hardship inflicted upon himself and his wife in having to cope without a slave whose ‘fine disposition and the many good qualities united together, rendered [her] the most valuable servant we ever had.'”

Even if a master allowed a courtship and marriage, there was always the threat that the husband or wife–or even the children–would be sold away.

C.S. Lewis once said, “I have married a lady suffering from cancer. I think she will weather it this time: after that, life under the sword of Damocles.” The sword of Damocles, an image of constant peril, is a reference to the sword that constantly dangled over a king’s throne, hanging by a thin hair plucked from a horse’s tail.

For slaves like Henry and Nancy, marriage was like this. A sword dangled just above their heads, threatening to slice through any bonds of love that they had formed.

But in the words of Mark 10:9–“What therefore God hath brought together, let not man put asunder.”Â

I imagine that not many masters allowed those words to be spoken at slave weddings.

By Doug Peterson