How the Church Helped Bring Down the Berlin Wall

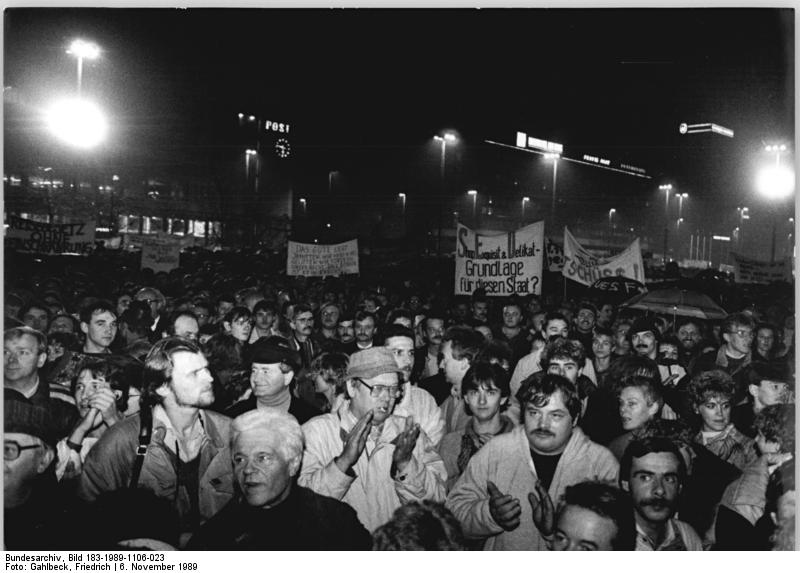

Protestors continued to fill the streets of Leipzig, Germany, on November 6, 1989. (Federal German Archives)

With the last name of “Fuhrer,” he made an unlikely German hero.

His full name was Christian Fuhrer, and this pastor led a movement that helped to bring down East Germany and the Berlin Wall. They called it “the Church From Below,” because this underground movement emerged from the ranks of the powerless and spilled out into the streets during the pivotal year of 1989.

Fuhrer was pastor of St. Nicholas Church in Leipzig, Germany, and in the early 1980s he formed Monday night prayer meetings for peace that started out with only a handful of people. As change swept through Eastern Europe in 1989, the prayer meetings grew, and the church attracted thousands of people who found it to be a safe place to air their grievances with the Communist party–the SED. The prayer meetings also spawned peaceful demonstrations that eventually packed the streets of Leipzig with 150,000 people–Christian and non-Christian alike.

The turning point was October 9, 1989, exactly one month to the day before the borders opened between East and West Berlin. Just two days earlier, on October 7 (the 40th anniversary of East Germany), a police crackdown on demonstrators had turned violent. As Fuhrer said in the book A Time to Speak Out, “We became witnesses of the most violent police action that we have ever personally experienced against a defenseless, nonviolent crowd of people who nonetheless, astonishingly, showed no fear.”

The police violence of October 7 didn’t prevent a massive turnout of people for the weekly prayer meeting on October 9 at St. Nicholas and four other churches in Leipzig. The downtown churches were all packed, but the streets were even more crowded–75,000 in all. The police and military had formed a cordon around St. Nicholas church, and the question in everyone’s minds was whether authorities would resort to “the Chinese solution.”

Earlier in the year, in June of 1989, the Chinese solution to demonstrations in Tiananman Square was to open fire on protestors and roll out the tanks. They used murder and massacre to keep the peace in China, and the Communist record in Eastern Europe over the years had not been any better. In 1953, the Soviets squelched an uprising in East Germany with tanks. In 1958, the Soviets squelched an uprising in Hungary with tanks. And in 1968, during the famous Prague Summer, the Soviets squelched the freedom movement in Czechoslovakia with–you guessed it–tanks.

On October 9, the day of the Monday prayer meeting in Leipzig, schools closed and hospitals stocked up with blood, anticipating the worst. If the demonstrators had turned violent in any way, it could very well have triggered the kind of massacre everyone feared. But the massive crowd remained peaceful. Whenever protestors shouted provocative slogans such as, “Stasi out!” (The Stasi were the secret police), Fuhrer says they were drowned out by a “billowing chant” of “No Violence! No violence!”Â

As it turned out, there was no violence, and the demonstration was allowed to go on without a shot fired. But Pastor Fuhrer said the greatest miracle of all was the reaction of some of the Communist party members who had infiltrated their prayer service that night. It was estimated that as many as 600 Communist party members had mixed into the crowd of 2,400 inside of St. Nicholas, and the next day some of them thanked him for the service.

As Pastor Fuhrer put it, these Communist party members “became part of the peace process themselves and were so impressed that they not only did not disturb the prayer service, they even joined in the reverent atmosphere…That is an incredible event. We could never have reached so many party members through any written effort or by any other means all at once, and something in writing would not have accomplished this; one simply had to have been there and experienced it.”

When police decided not to crack down on Leipzig demonstrators with tanks and bullets on the night of October 9, the tide turned, setting the stage for the demise of the Berlin Wall one month later. It’s no wonder that Leipzig became known as “the city of heroes.Â

By Doug Peterson