Elijah Lovejoy’s Last Stand

Mobs had already destroyed Elijah Lovejoy’s printing press three times, and they were aiming for a fourth time in November of 1837.

Lovejoy, a Presbyterian minister, had riled up people in St. Louis for his abolitionist views in his newspaper, The St. Louis Observer. So he crossed state lines, into the city of Alton in the free state of Illinois, and kept on publishing, this time in the publication he named The Alton Observer. But even though Alton was in a free state, much of the population was made up of people sympathetic to the southern slave system. So, on November 7, 1837, a mob converged on Gilman’s Warehouse, where Lovejoy had hidden yet another printing press–his fourth.

The mob put a ladder up against the warehouse, and a man climbed to the roof, intending to set it ablaze. But Lovejoy and a friend, Royal Weller, dashed out of the warehouse and pushed over the ladder. Armed with guns, they also fired into the mob, killing a man named Bishop.

This ignited the attackers, so Lovejoy and Weller retreated inside the warehouse. And as the pro-slavery forces set the ladder back up again, Lovejoy and Weller charged outside once again and made another move to push it over.

They didn’t get far. Weller was wounded, but Lovejoy took five bullets and died. Some have called him the “first casualty of the Civil War,” even though the War Between the States was another 24 years in the future.

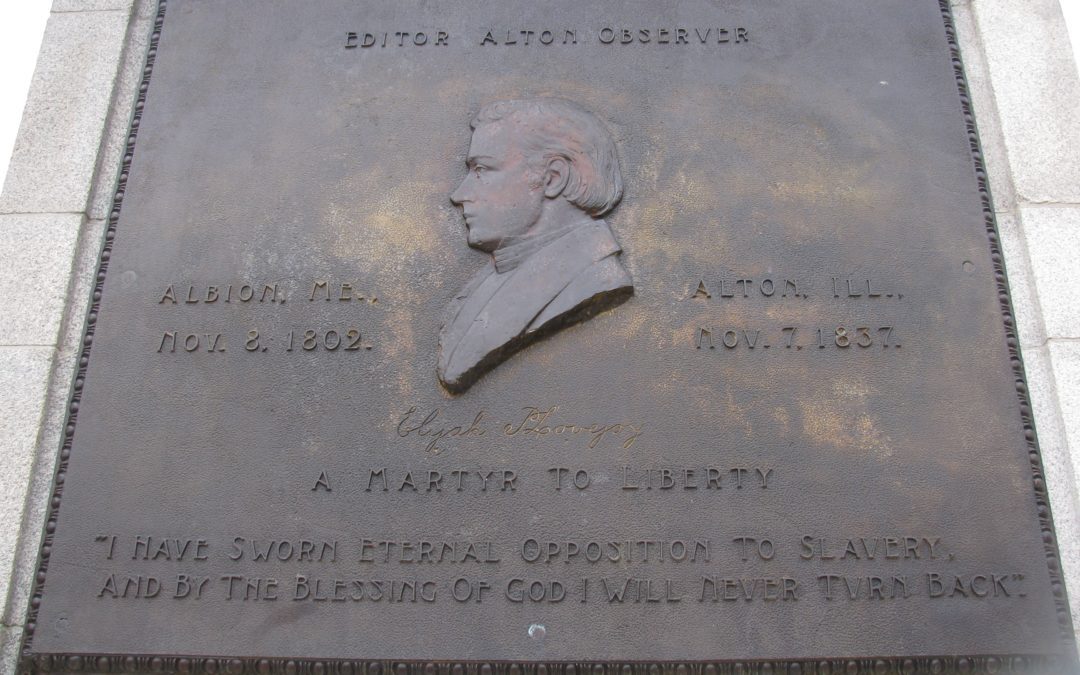

I was in Alton recently, hiking along the Mississippi River, and I had a chance to see Lovejoy’s grave and monument. Today, he is a recognized hero with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame and his name on the Southern Illinois University Library. (Some people even proposed that the entire university be named after him.)

Five days before his death, Lovejoy gave a speech to the people of Alton, which included these prophetic lines:

Five days before his death, Lovejoy gave a speech to the people of Alton, which included these prophetic lines:

“I know you can tar and feather me, hang me up, or put me into the Mississippi, without the least difficulty. But what then? Where shall I go? I have been made to feel that if I am not safe at Alton, I shall not be safe anywhere. I recently visited St. Charles to bring home my family, and was torn from their frantic embrace by a mob. I have been beset night and day at Alton. And now, if I leave here and go elsewhere, violence may overtake me in my retreat, and I have no more claim upon the protection of any other community than I have upon this; and I have concluded, after consultation with my friends, and earnestly seeking counsel of God, to remain at Alton, and here to insist on protection in the exercise of my rights. If the civil authorities refuse to protect me, I must look to God; and if I die, I have determined to make my grave in Alton.”

By Doug Peterson