Shell Shock Diagnosis Emerges From the Horrors of World War I

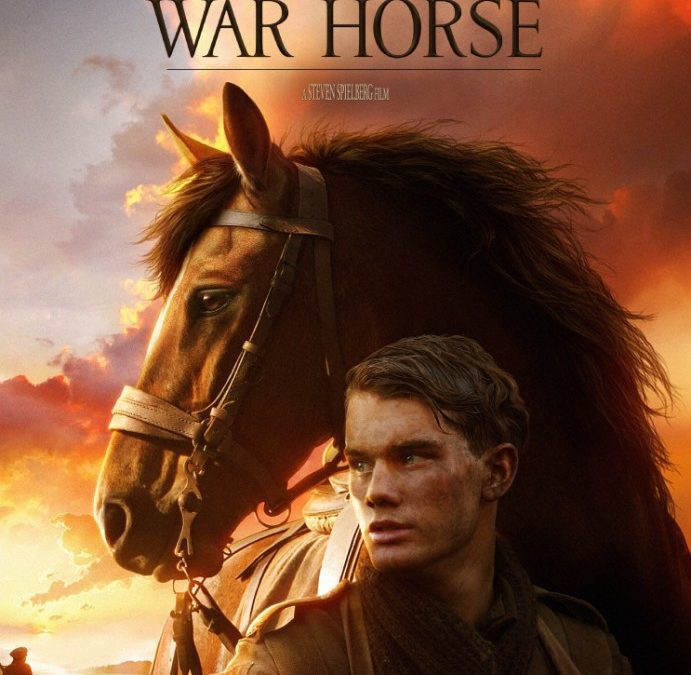

I watched the Stephen Spielberg movie, War Horse, on the same weekend that I taped the latest episode of the PBS show, Downton Abbey, giving me a double-dose of World War I. The trauma of shell shock and trench warfare figured prominently in both stories, bringing to mind an article that I wrote a year and a half ago for the University of Illinois College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

I watched the Stephen Spielberg movie, War Horse, on the same weekend that I taped the latest episode of the PBS show, Downton Abbey, giving me a double-dose of World War I. The trauma of shell shock and trench warfare figured prominently in both stories, bringing to mind an article that I wrote a year and a half ago for the University of Illinois College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

“The signature feature of the World War I battlefield was the trenches, where a squadron might stay fixed in one place for weeks, followed by a sudden outburst of intense, almost suicidal, activity,” said U of I history professor Mark Micale when I talked to him about the book he edited, Traumatic Pasts. “With bayonet and grenades in hand, they would have to charge over the top into a wall of machine-gun fire”–the kind of charge graphically depicted in both War Horse and Downton Abbey.

This “anticipatory fear” was a key element behind the trauma, Micale explained to me. “Anxiety works on the mind, particularly if, while you are waiting, you see the deadly damage the war has done on fellow soldiers. In the trenches, they would have seen death all around them. It’s clear from the soldiers’ writing in World War I that the only thing they knew is that they were alive then and there. They didn’t know if they would be alive next week or tomorrow or even five minutes from then.”

In World War I, traumatized soldiers shared many common symptoms, such as speaking difficulties, problems with vision, facial twitches, walking disorders, convulsive vomiting, or severe cramps. They also displayed the kind of symptoms associated with present-day Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD–insomnia, violent nightmares, and flashbacks.

During World War I, the malady went under many names, such as traumatic hysteria, soldier’s heart (because of unexplained heart palpitations), or war exhaustion. But the alliterative label that stuck was “shell shock.”Â

“If you think about it, the shell shock label illustrates something fascinating,” he said. “It makes it sound like soldiers are suffering from an actual physical injury. An artillery shell exploded nearby, and the concussive force of the blast damaged the nervous system or brain.”

By making the injury seem more physical than psychological, the term “shell shock” made the disorder more acceptable to both patients and the population.

“At that time, to have said it was all in their head would have suggested borderline insanity or moral weakness–cowardice even,” Micale said. The shell shock label “camouflaged its real psychological nature,” he added, although it also meant at least that the disorder was finally being diagnosed and treated.

In the early part of the 20th century, psychiatrists could do little more than describe the symptoms and diagnose the problem, for treatments were rare–and primitive. Some doctors applied electro-shocks to affected areas. If a soldier had difficulty speaking or walking, for instance, doctors shocked his vocal cords or legs.

“It sounds horrific to us today, but the idea was that you literally shock the soldier-patient back into functionality,” Micale explained. “If one fear caused them to freeze up, a counter-fear would unfreeze them.”

Micale said trauma-induced disorders didn’t receive as much attention in World War II because it was a far more mobile war, with armies sweeping up the boot of Italy or across France after the D-Day invasion–in contrast to the stationary trench warfare of the previous conflict. Staying mobile reduced the anticipatory fear. The shell shock issue did not come back to the forefront until the Vietnam War, when Hollywood gave the American public the iconic image of the veteran returning home as a broken soldier.

The diagnosis of PTSD emerged at this time, officially being adopted in 1980 by the American Psychiatric Association. Today, the military has gone beyond simply offering treatment programs.

“They also have campaigns to convince soldiers and their families that PTSD is for real,” Micale said. “The message is to know what’s happening to your body and mind and not to feel alone or ashamed of what is, after all, a very human response.”Â

By Doug Peterson