Richmond Was Not Gone With the Wind

I did a flurry of radio interviews a few weeks back just prior to my book signing at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. And one of the longest interviews was with Alan Jarand from the RFD Radio Network out of Bloomington, Illinois.

I did a flurry of radio interviews a few weeks back just prior to my book signing at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. And one of the longest interviews was with Alan Jarand from the RFD Radio Network out of Bloomington, Illinois.

Alan said he usually skims books before interviews, but he was drawn into The Disappearing Man and wound up reading it page by page. I liked hearing that. But what struck me is that, like me, he was shocked by how different the urban slave system was from his preconceived notions.

“It’s a fascinating tale,†Alan said of The Disappearing Man. “It’s more than just a story about Box Brown and his escape, but it gives you such an inside look at life in the pre-Civil-War South.”

If you want to check out Alan’s interview with me, here is a link to the podcast. You can find the interview almost exactly halfway through the podcast, so jump ahead to the midway point to find it.

http://74.220.207.66/~stretch8/rfd/podcasts/rfd-110318-b.mp3

I had much the same reaction as Alan when I first began to research Henry Brown’s story. In Henry’s two first-person narratives, one written in 1849 and the other in 1851, he mentioned being paid; he said something about doing “overwork”Â; he described living in a tenement away from the master; and he said he once wandered off the factory grounds without anyone catching him (“losing time” they called it). This sounded a lot different from the plantation system that Americans are familiar with from movies like Gone With the Wind.

About 90 percent of slaves lived in rural areas and most of those were on plantations, so our common perception does make some sense. But I was completely unaware of that forgotten 10 percent–the urban slaves.

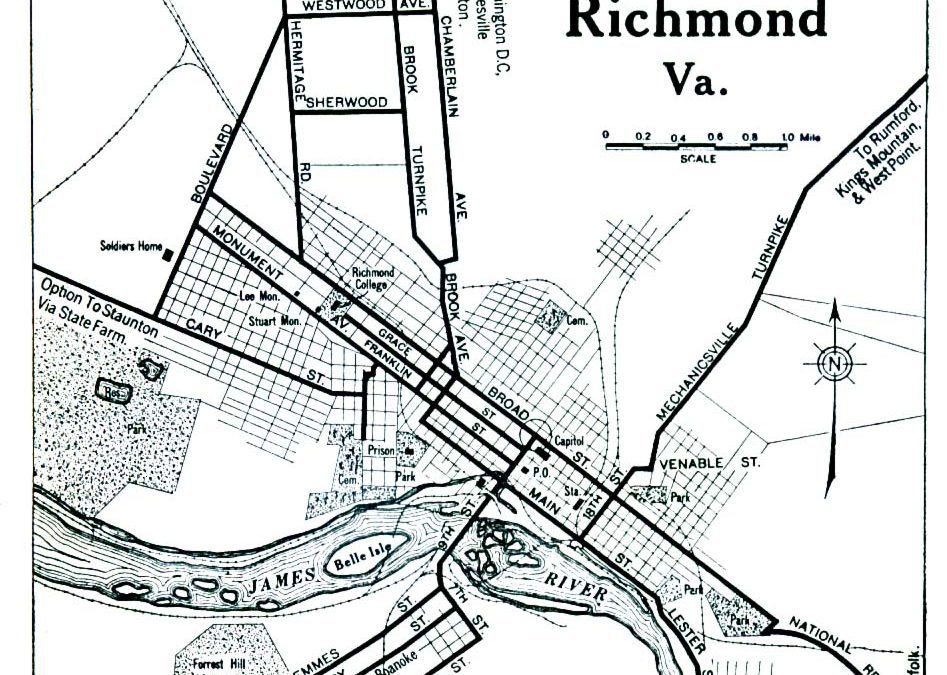

When Henry came to Richmond at 15 years of age in 1830, the city’s population was about 16,000–6,000 of whom were slaves and 2,000 of whom were free blacks, says Midori Takagi in her book, Rearing Wolves to Our Own Destruction. White authorities established all sorts of laws to control the interactions among the three groups–slaves, free blacks, and whites–but it was difficult maintaining control in a sprawling urban area.

From Takagi’s book and other sources, I discovered that slaves in Richmond were paid a stipend, which many used to board out away from the master, typically in the city’s Shockoe Bottom area near the James River. However, the stipend often wasn’t enough to live on, so to make extra money some slaves did “overwork,” which was essentially overtime. As a result, the days were long. Henry describes 14-hour workdays at the factory in the summer and 16-hour workdays in the winter (six days per week).

Slaves in Richmond were given little tastes of freedom. But this just made the hunger for freedom that much stronger and may have helped to undermine the slave system. As the Mississippi Quarterly put it, “Industrial employment allowed blacks to carve out a degree of autonomy that sowed the seeds for slavery’s potential demise.”

By Doug Peterson