Music Links Henry Brown to 21st Century Abolitionists

Henry couldn’t help but notice her. He hadn’t seen the girl before in the church choir, but there she was, rocking and swaying and stepping with the music….Henry stole another look down the row. The girl did not notice his attention, so he drew away and tried to refocus on his singing.

‘Steal away, steal away, steal away to Jesus! Steal away, steal away home, I ain’t got long to stay here! My Lord calls me, He calls me by the thunder; The trumpet sounds within-a my soul, I ain’t got long to stay here.’

Minutes later, Henry ventured another look, this time letting his eyes linger. If she sensed his eyes on her, she didnt give it away. Her eyebrows arched above almond eyes.

‘Steal away, steal away, steal away to Jesus! Steal away, steal away home, I ain’t got long to stay here! Tombstones are bursting, poor sinner stands a-trembling; The trumpet sounds within-a my soul, I ain’t got long to stay here.”

* Â * Â *

If Henry Brown’s life ever made it into film, music would have to play a major role. Henry, the slave who mailed himself to freedom in 1849, was a powerful singer, one of the finest voices in the choir of First African Baptist Church in Richmond.

If Henry Brown’s life ever made it into film, music would have to play a major role. Henry, the slave who mailed himself to freedom in 1849, was a powerful singer, one of the finest voices in the choir of First African Baptist Church in Richmond.

For many slaves, music was their only escape–their only relief during the grueling workdays. In the tobacco factory where Henry toiled, the overseer John Allen did not abide slaves singing, but that was not always the case in other factories and on most plantations. In fact, Shane and Graham White note in The Sounds of Slavery that most owners realized that slaves would work harder if they were allowed to sing. The singing also confirmed in the owners’ minds the illusion that their slaves were actually “happy” in their work, so they often approved of it.

Given Henry’s great voice, I tried to work music into The Disappearing Man wherever I could; and I did so using lyrics of actual nineteenth-century slave songs. I dipped into two sources for these songs: American Negro Songs (first published in 1940) and Slave Songs of the United States (first published in 1867). In doing so, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that Slave Songs of the United States was compiled, in part, by Lucy McKim Garrison, daughter of the abolitionist who helped Henry Brown escape–J. Miller McKim.

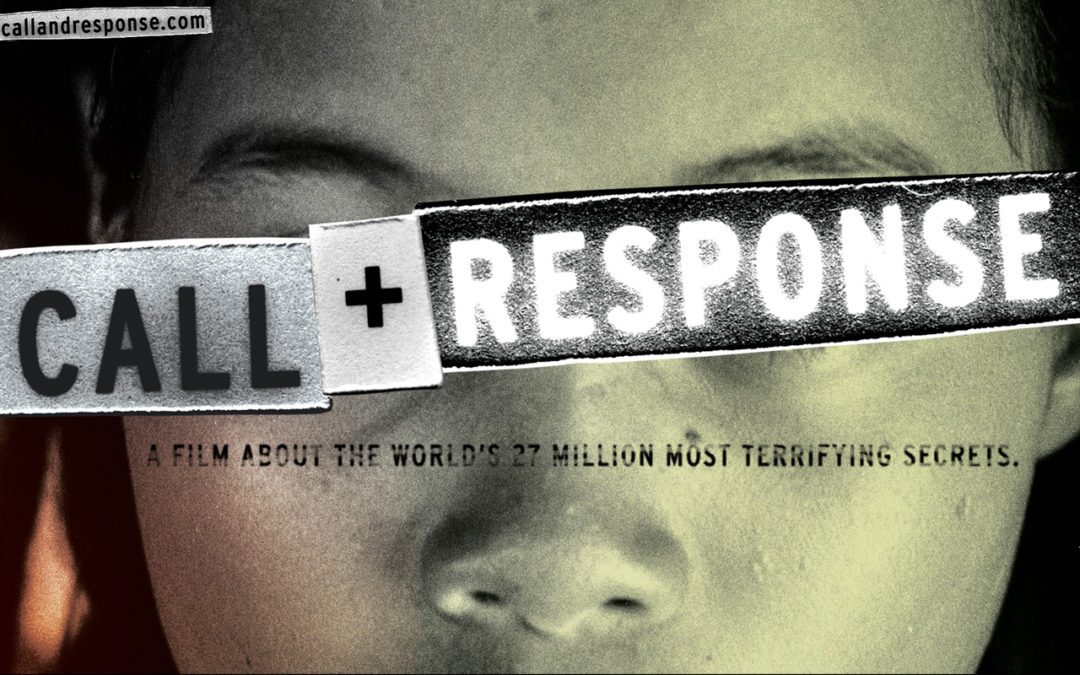

One of the most distinctive forms of song among slaves was the “Call and Response.” According to The Sounds of Slavery, slaves would “sing in response to, and in ‘conversation’ with, one or more of the other singers.” Call and Response is just what it sounds like. One musical phrase follows in response to another musical phrase. Therefore, it is only fitting that a recent documentary on modern slavery would be entitled Call and Response.

This powerful documentary sends out a call and awaits a response from the viewers. As the documentary points out, human trafficking is the fastest growing crime on the planet today, as over 2.2 million children are sold in the sex trade every year. The documentary also makes the startling point that “There are more slaves today than at any time in history.”

Human trafficking is a difficult subject to watch. No doubt about it. But I had a chance to preview Call and Response, and the music in this documentary made it tolerable to sit through the difficult parts, providing the necessary relief just when the information seemed overwhelming. The documentary features such musicians as Moby, Switchfoot, Natasha Bedingfield, Justin Dillon, Hasidic reggae singer Matisyahu, and many more.

I encourage you to check out Call and Response; and if you live in the Champaign-Urbana area, take a look at the documentary at the Art Theater at 2:30 p.m. this coming Sunday, March 27.

Moses heard the call and he responded. This planet needs a Moses for today–a few hundred thousand of them, in fact, to answer the call and lead today’s slaves through the parted waters.

By Doug Peterson