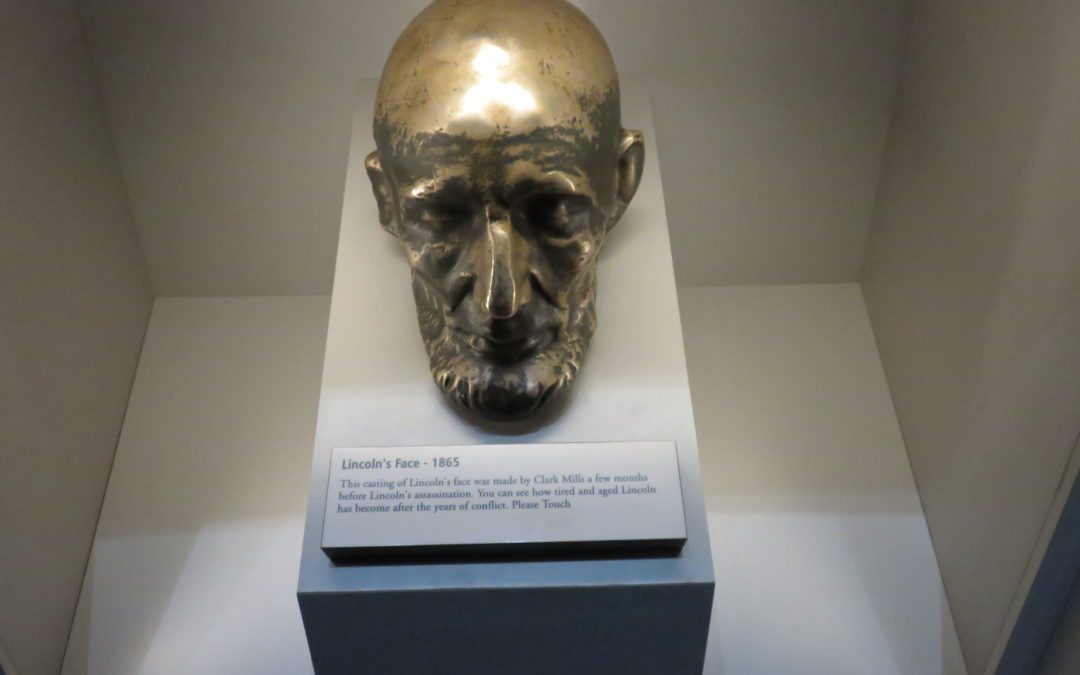

Abraham Lincoln had two “life masks” created–one in 1860 before the Civil War began and the other in 1865, when the war was ending. The masks were made to preserve what he really looked like in life, but the difference between the two masks was shocking.

Abraham Lincoln had two “life masks” created–one in 1860 before the Civil War began and the other in 1865, when the war was ending. The masks were made to preserve what he really looked like in life, but the difference between the two masks was shocking.

The 1860 life mask showed “a man young for his years,” said John Hay, Lincoln’s assistant. The second life mask, on the other hand, showed a man beaten down by the sorrow of war.

In fact, when the famed sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, saw the 1865 life mask, he was convinced that it was a death mask. The features of the face looked like that of a man who had died.

The Civil War began in 1861, and four years of brutal war left a toll on Lincoln’s health and appearance, just as it had done to the scarred American landscape. The death of Lincoln’s child, Willie, only added to his woes during the war years.

Ironically, Lincoln was also known for his witty stories and sense of humor, but as president he carried a heavy burden. The responsibility of sending so many soldiers off to their deaths in a war to end slavery and preserve the Union did its brutal work on Lincoln, and you could see it in his face.

I recently visited the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois, where I saw the two life masks on display. I highly recommend the Lincoln Museum if you’re ever in central Illinois, but make sure you check out the tremendous multi-media show, “Lincoln’s Eyes,” which traces the president’s life and the toll of the war on Lincoln as shown in photographs.

Seeing the life masks and how Lincoln’s sorrow was reflected in his appearance made me reflect on the nature of leadership and the ways in which he absorbed the pain all around him. Despite his sorrow, Lincoln managed to bring the country back together and take down the system of slavery.

It was an incredible feat of leadership.

Recently, I also read about an entirely different land that faced a crisis between North and South, but the leadership in this country led to a much different outcome than our Civil War. Correction: I should say the lack of leadership led to a different outcome. Instead of healing and coming back together, this other land remained divided for a couple of hundred years.

I’m talking about the division of Israel and Judah following the death of King Solomon in 922 B.C.

With Solomon’s death, the southern tribe of Judah embraced his son Rehoboam as the new king. But the northern kingdom of Israel protested Rehoboam’s heavy taxation and the use of forced labor for building projects–practices that began under Solomon’s rule. Elders of various Hebrew tribes met with Rehoboam and laid out their complaints.

What was Rehoboam’s response?

He rejected the requests and vowed to get even stricter and harsher on the people.

This failure in leadership led to a dramatic split between Israel in the north and Judah in the south. The result was a royal mess, with Rehoboam as king in the south and Jeroboam as king in the north. To make matters worse, Jeroboam erected two new temples to compete with the Temple in Jerusalem, and they created two golden bulls–symbols of pagan worship.

No wonder the period of the two kingdoms, from 922 to 722 B.C., produced a line of prophets (Elijah, Elisha, Amos, Isaiah, Hosea, and Micah) who were angry about what was going on in the land. It all stemmed from a massive collapse of leadership.

Contrast Rehoboam’s strict approach toward the rebels in Israel with Lincoln’s strategy immediately following the end of the Civil War. While some in the North called for retribution against the rebellious South, Lincoln called for reconciliation. The famous words of his second inaugural address said it all: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds.”Â

One month after this speech, Lincoln was assassinated. He was now ready for his death mask.

By Doug Peterson